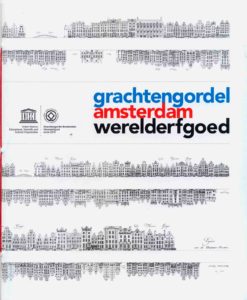

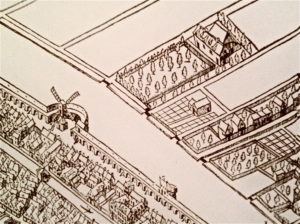

The Canal District is the monumental result of an innovative 17th-century town expansion. The masterpiece of urban development was created on 90 artificial islands, and connected by no less than 1.500 bridges. The construction of the canal ring in 1613, and its extension in 1660 prompted Amsterdam’s elite to move from the old city center to the new ‘Gold Coast’. Today, you can follow in their footsteps and explore the highlights of the ‘Venice of the North’. After all, the Italian city is also a town full of canals and was for centuries a powerful trading hub with a rich architecture. Just like Amsterdam

In 2010, the Canal District was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list. Some of the canal houses and national landmarks in this area are known all over the world. Their facades served as an inspiration for the designers of miniature houses in Delft Blue. The souvenirs became a phenomenon in the world of travel, after KLM Royal Dutch Airlines presented them as a gift to its Business Class passengers.

1.The smallest house in Amsterdam

Location: Singel 7

You are now standing in front of the smallest house of Amsterdam. Can you see it? It’s on number 7. But first let me tell you about this canal. It’s called the Singel canal. In 1480, this canal was dug to encircle medieval Amsterdam. About hundred years later, the city was expanded beyond this moat to create more room to built houses. The first part of the Herengracht, the canal behind the houses to the west, was dug in 1585. However, an economic crisis thwarted the sale of building plots along the new quayside and the entire project slowed down dramatically.

In the Dutch Golden Age, the quayside finally became prime real estate for the up-and-coming merchant elite who, in their attempts to outdo their neighbors and other aristocrats, filled this street with one grand house after another. The only problem with that were the taxes; the broader your facade, the higher the tax on your house. Yet, this did not stop the merchants from building their grand houses and it was this extra income for the city council that financed the construction of the famous canal ring we see today.

The narrowest facade in Amsterdam is located right here at Singel 7 and measures just over one meter wide. A standard door is about 90 centimeters, so that does not leave room for much else. But once you step inside however, this small house gradually increases to a more comfortable width of around three meters. This strangely expanding house was not a construction error, but an early form of tax evasion! The owner had built his facade as narrow as possible to reduce the amount of tax he had to pay. And although the house behind it was larger, he only had to pay tax on the frontage.

We are walking towards the north to the bridge. This is bridge number 14, behind the Haarlemmer sluice.

- Haarlemmer Sluice

Bridge No. 14 opposite Nieuwendijk 2

This is the Haarlemmer Sluice. It was built in 1602, as part of the sea dyke running along the waterfront. You must imagine that in those days, the whole area to the north, where Central Station is, was water. In this way Amsterdam had a direct connection with the North Sea. Until the 17th century, the water level in the city was determined by high and low tide. However, after the installation of eight sluices, the lock-keepers could influence the water level. The Haarlemmer Sluice can close off the Singel. At the end of the canal, the flower market, the water can flow into the River Amstel.

Water levels in Europe are determined according to a standard that originated in Amsterdam. In 1684, mayor Joannes Hudde decided to determine the average water level. All eight locks in the sea dyke were fitted with a white marble stone with a horizontal line exactly cut at the height of the top of the sea dyke. That way, the lock-keeper knew exactly when the gates needed to be opened and closed, to prevent the city from flooding. This standardization of the water level is called N.A.P. (meaning ‘Normaal Amsterdams Peil’ or standard Amsterdam water level) and its level is used in Germany, Sweden, Norway and Finland.

Of the eight marble stones marking the water level in 1684, only the stone near the Eenhoorn Sluice (or Unicorn Sluice), at the beginning of the Prinsengracht, is still in its original place. If you like to see the white marble stone yourself, continue your walk across the bridge into the Haarlemmerstraat until the next bridge. It’s Bridge 314, opposite Haarlemmerstraat 150. But we’re going another way. Let’s go.

Cross the bridge, pass the stall, where they sell the best herring in town, turn left, and walk about 50 meters to the intersection with the Brouwersgracht. This canal marks the northern border of the Canal District, connecting the Singel, Herengracht, Keizersgracht and Prinsengracht. Turn right.

This is the Brouwersgracht (The Brewers’ Canal). In the 17th century, the Brouwersgracht served as a site for ships returning from Asia with spices and silks, therefore this canal had many warehouses and storage depots. The canal is named after a number of beer breweries which were prevalent in the area because of its easy access to fresh water shipments.

Opposite Brouwersgracht number 54, turn left and cross the small bridge to Herengracht number 1.

3. Herengracht 1

Let me tell you a bit more about Amsterdam’s history. Towards the end of the 16th century, Amsterdam was on the brink of becoming the most important center of trade in the world. The city burst with energy and entrepreneurship. Elsewhere in Europe, the atmosphere was less optimistic. Spanish soldiers loyal to King Philip II hunted down all those who weren’t Catholic. After the fall of Antwerp in 1585, thousands fled to the free northern sanctuary of Holland, and tolerant Amsterdam became a cultural melting pot. But housing these immigrants was a problem.

The first section of the Herengracht, where we stand now, was dug to create some extra living space. Members of the city council bought up land for themselves in order to flip it later at huge profits. The spade had yet to go into the ground, but Amsterdam’s elite knew exactly what it wanted once the canal has been dug: ‘beautiful mansions and houses’ for ‘retired and other wealthy people.’

Let’s continue our walk. We’ll pass some of the oldest historic buildings on this side of the canal. At number 43, you’ll see the 16th-century spout gables of two storage depots, which were turned into houses named Noah’s Ark and ‘t Fortuijn (or Fortune). The two warehouses have been built in 1580. At that time, the chic Herengracht was just a broad ditch. A few blocks further, we’ll pass a quaint merchant’s house at Herengracht 81, dating back to 1590, and rebuilt in 1626. It’s one of the oldest houses in Amsterdam.

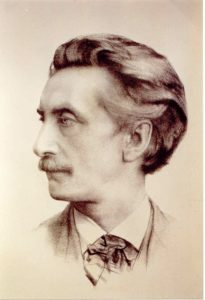

You see that little alley on your left? That’s the Korstjespoortsteeg. On the top floor of a small house at number 20, the famous author Eduard Douwes Dekker was born, on March 2, 1820. He was a boy of simple descent who rose to fame after his novel ‘Max Havelaar’ was published. The book is a critical essay about the Dutch colonial rule in what is now Indonesia and can be compared to ‘Uncle Tom’s cabin’. In the Multatuli House, the birthplace of Dutch most important 19th-century writer, you can find the Multatuli Museum and the Multatuli Society.

Continue along Herengracht.

- Herengracht 95 (KLM-house No. 57)

Before we reach our next stop, at Herengracht 95, I want to tell you a bit more about this canal.

The Herengracht got its present name when the construction of the canal ring was started in 1613. The name Herengracht refers to the first speculators, the gentlemen who ruled the city. It was to be the showpiece of the canal-ring project and for this reason the bridges spanning the water were constructed of stone rather than timber.

There was much interest in the land on the banks of the Herengracht. The number 95 plot, at your left, was bought by a merchant who made a fortune in the Russian calf and goat leather trade. In 1614, he commissioned a master carpenter to build him a 5.6 meters wide house, with a stepped gable and storage lofts with hoist doors on each of the four floors. In 1790, the facade of number 95 was modernized, and its gable replaced by a classical one with a straight cornice. The most striking new element was a Louis XVI oval shield with a golden star and a garland of laurels. It was the symbol that gives the house its present name: The Star. And it’s also the name of KLM house No. 57.

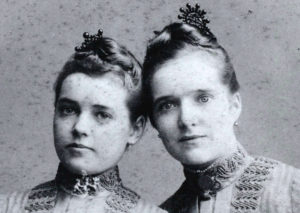

Mid-19th century, Johannes Went bought Herengracht 95 and moved in with his wife and children. He was the pater familias of a socially-engaged family, and plenty of music was made at home. His eldest daughter, Louise, was a talented singer and in 1888, she performed at the grand opening of Amsterdam’s brand new Concertgebouw. More than for her musical voice, however, Louise Went was known for her critical voice and pioneering social housing schemes.

Mid-19th century, Johannes Went bought Herengracht 95 and moved in with his wife and children. He was the pater familias of a socially-engaged family, and plenty of music was made at home. His eldest daughter, Louise, was a talented singer and in 1888, she performed at the grand opening of Amsterdam’s brand new Concertgebouw. More than for her musical voice, however, Louise Went was known for her critical voice and pioneering social housing schemes.

Just a short walk from her parental home lay the working-class neighborhood Jordaan, where Louise’s sense of social responsibility took hold. She became an authority in social work, and co-founded the world’s first school for social workers. After her death, streets in both Amsterdam and Leiden were named in honor of this equal rights activist, who did so much for the socially disadvantaged.

You see that a brownish painted canal house, on the other side of the Herengracht? It dates back to 1614. It’s another KLM-house, No. 56.

- Herengracht 64 (KLM-house No. 56)

On this spot, Jan van Alderwerelt, a 26-year-old trader in woolen fabrics, purchased several plots of land from a speculator and commissioned the construction of a row of four houses. The name ‘De Werelt’ (or The World) appears on each façade and globes were placed on the roofs, in reference to his family name.

After his death, his oldest son inherited the houses. Number 64 was rented out to Frederick Rihel. The new tenant was a merchant from Strasbourg whose management skills landed him a position at the helm of the trading company, Bartolotti, just a short walk from his house at Herengracht 170.

After his death, his oldest son inherited the houses. Number 64 was rented out to Frederick Rihel. The new tenant was a merchant from Strasbourg whose management skills landed him a position at the helm of the trading company, Bartolotti, just a short walk from his house at Herengracht 170.

Rihel was highly respected – a man of stature. In 1664 he commissioned Rembrandt van Rijn to immortalize him in a striking uniform, including a plumed hat, a leather coat over a jacket with gold-embroidered cuffs and a sash. The painting took was the centerpiece of his reception hall at Herengracht 64. Today, Rembrandt’s masterpiece can be admired in London’s National Gallery.

Continue along Herengracht.

6. Herengracht 101 (KLM-house No. 58)

Of all canals, the Herengracht was the most prestigious location to live. In 1631, a dream came true for cloth trader Cornelis Jansz Blaeuwenduijff. At auction, he bought a piece of land at number 101, to build a stately home of 5.30 meters’ width, with two floors and a storage loft. The lower register of the stepped-gable façade was made of wood. Above the entrance, the owner hung a sign with a picture of a bird and his name Blaeuwe Duijff (meaning Blue Pigeon).

In the early 1950s, after centuries of being just an ordinary residential house, the historic building changed function and became a hotel. Hotel Post was named after the owner and it attracted a lot of American and Canadian soldiers, who were on leave in Amsterdam. In 1979, Herengracht 101 was split into several separate apartments.

In the early 1950s, after centuries of being just an ordinary residential house, the historic building changed function and became a hotel. Hotel Post was named after the owner and it attracted a lot of American and Canadian soldiers, who were on leave in Amsterdam. In 1979, Herengracht 101 was split into several separate apartments.

Continue along Herengracht.

7. Herengracht 163

Towards the end of the 16th century, the plans for digging the first part of Herengracht were made, trader Cornelis Jacobsz Witsen rushed to take an option on a building plot. As part-time regent of the city council, Witsen had insider knowledge, as he knew that at some time in the future a lot of money would be made after the construction of the canals.

The powerful Witsens quickly acquired a lot of influence in the Dutch Golden Age and, thanks to a few sons who became mayors of Amsterdam, it was as if the family had become court purveyor to the city council. At Herengracht 163, further to your left, Cornelis Witsen built a house with a sober stepped gable. In the 17th century, through inheritance, it eventually came into the possession of the extremely wealthy Balthasar Coymans, whose family, like the Witsen dynasty, also belonged to Amsterdam’s elite.

In 1721, when the house was bought by wine merchant Jan Willemson, it received a new name: The Hochheimer Feeder Vat, after the large barrels which were used to transport wine from the German Rhine region. Just look up at the gable. Before the eye-catching yellow gable stone could be installed, Willemson had some changes made to the design of the façade. The stepped gable was removed and replaced by a modern neck gable, with beautifully sculpted wings.

Continue along Herengracht.

8. Herengracht 203 (KLM-house No. 53)

In the 17th century, the construction of the canal ring prompted many among Amsterdam’s elite to move from the old city center to the new ‘Gold Coast’. In 1618, wine merchant Wolphert Webber commissioned the most celebrated architect of the day, Hendrick de Keyser, to build a prominent merchant’s house at Herengracht 203. It’s at your left. In those days, business was booming. Originally Webber came from the Elzas region and its wines were immensely popular among the affluent Dutch. His profits in the wine trade, and his shares in the Dutch East India Company, made him a very wealthy man. The prime location of his house on the Herengracht and its size led to a whopping annual tax bill of 400 guilders.

Continue along Herengracht, turn right into Raadhuisstraat and cross the bridge. Walk west towards the Westerkerk.

9. Westerkerk

The Keizersgracht canal is 31 meters wide, and is the second and widest of the three major waterways of the Canal District. You can see that the houses along this canal are not as posh as those on the Herengracht (the Gentlemen’s Canal). We’ll see the third canal a bit further. It is called the Prinsengracht (or the Prince’s Canal).

Do you see that robust tower in front of you? That is tower of the Protestant church Westerkerk, or West Church, which is topped with the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Emperor. In the 15th century, Maximilian I was the archduke of Austria and ruler of the Low Countries. The canal right and left of you is called the Keizersgracht, or Emperor’s Canal, and it was named in Maximilian’s honor. In 1484, the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I traveled to Amsterdam to prey for recovery from an unknown illness. In the 14th-century, the medieval city had become a place of pilgrimage after a divine miracle took place here. Many pilgrims from all over Europe went to visit a Catholic shrine seeking cures and spiritual help. Maximilian I was healed, too, and he granted the city of Amsterdam the right to use his Imperial Crown in its coat of arms.

Cross the bridge and walk past the West Church, to the next bridge.

10. Nieuwe Wercksbrug

In front of you is is one of the fourteen bridges spanning the Prinsengracht. This canal was dug in 1612 and is named after Prince Maurits, the Prince of Orange. When the first section was dug in 1615, its banks were strengthened using sand from the working-class neighborhood Jordaan, a stone’s throw away from here to the west, and from Het Gooi was used, a posh region some 25 km southeast of Amsterdam.

Originally, the area beyond Prinsengracht was called Het Nieuwe Werck (The New Work), which is also the name of this bridge. The neighborhood was ideal for poor immigrants looking for work, as the houses were cheap and demand for craftsmen was high. The neighborhood later became known as the Jordaan.

Looking at a map of the Jordaan, you can see from the street pattern exactly where the 16th century ditches used to be. The houses were built as close to the water as possible. Boats were the quickest mode of transport, after all. Almost every square meter of the neighborhood was used. Ground-floor and upper apartments, and even cellars, were sold or rented separately. In some cases, eight people lived in one room.

Cross the bridge and turn left into Prinsengracht.

11. Prinsengracht 305 (KLM-house No. 62)

A bit further, on the other side of the canal, on Prinsengracht 305, we’ll see another KLM House. Around 1616, one of the first merchant’s houses erected at this part of the Prinsengracht, was built at No. 305. More than a century later, in 1720, the historic building was given a new, Louis XIV façade. Its most notable feature is the top, with a raised cornice in the shape of a clock gable. Decorative vases were placed on either side of the crest. The style elements are inspired by the vases of Classical Antiquity, which in Greek and Roman times were filled with lamp oil to illuminate dwellings.

The sculpted gable top was carved by the gifted stonemason, Anthonie Turck. He has left his mark all over the city of Amsterdam. In those days, his striking and monumental ornaments caused a sensation in the world of sculpture.

The sculpted gable top was carved by the gifted stonemason, Anthonie Turck. He has left his mark all over the city of Amsterdam. In those days, his striking and monumental ornaments caused a sensation in the world of sculpture.

Turck’s invention of the richly decorated, raised cornice (like you see above), and the neck gable with floral motifs in the scrolls unleashed nothing less than a sculptural revolution. Prinsengracht 305 was a much sought after piece of real estate and over the centuries, its value increased tenfold. Continue along Prinsengracht.

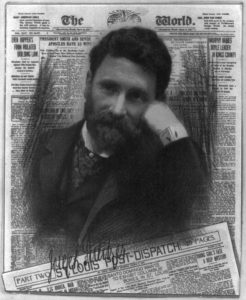

During the 1960s, the Prinsengracht was a rather bleak, cheerless area. A  number of buildings near the Westertoren were used as warehouses, which added to the dreary streetscape. In 1970, Herbert Pulitzer, an American businessman and the great-grandson of famous publisher Joseph Pulitzer, purchased a row of nine 17th and 18th-century canal mansions and combined them to create the Pulitzer Hotel, at Prinsengracht 315. Initially, Prinsengracht 305 was part of the hotel, too. In the years that followed, the five-star hotel expanded further to incorporate no less than 25 internally connected canal houses.

number of buildings near the Westertoren were used as warehouses, which added to the dreary streetscape. In 1970, Herbert Pulitzer, an American businessman and the great-grandson of famous publisher Joseph Pulitzer, purchased a row of nine 17th and 18th-century canal mansions and combined them to create the Pulitzer Hotel, at Prinsengracht 315. Initially, Prinsengracht 305 was part of the hotel, too. In the years that followed, the five-star hotel expanded further to incorporate no less than 25 internally connected canal houses.

Continue along Prinsengracht.

12. Reesluis

This bridge across this part of the Prinsengracht is called Ree-sluis. Its named after the Reestraat (or Deerstreet) to your left, which refers to the artisans and traders who in this area were active in dealing with animal hides for the leather industry.

The bridge is the prime location for people to watch a renowned open-air classical concert held annually in August. The orchestra and world-class artists perform on a floating platform in the canal. The audience can enjoy the concert from this bridge and the canal banks, or, like many locals, come in a little boat and anchor nearby the platform. As perhaps one of the few concerts where your seat is also a boat, the Prinsengracht Concert is a truly unique experience. The canal is also the fabulous floating stage for the annual Amsterdam Gay pride, with a parade of boats and their exuberantly dressed crews.

Continue along the Prinsengracht, cross the bridge and keep walking south.

13. The Houseboat Museum

Prinsengracht 296 K

Well, a bit further, you’ll find a very special museum. There are over 800 houseboats in the city center and if you want to see what it’s like to live in such a traditional Dutch canal boat, then visit the Houseboat Museum. Until the 1960s, the 23 m. vessel ‘Hendrika-Maria’ primarily transported sand and gravel, after which it was converted into a houseboat. A number of houseboats still dump toilet and other waste water into the canal. The city council aims to have all canal boats connected to the sewer system by 2016.

Continue along Prinsengracht.

14. Smelly canals

Just walk to the bridge in front of you and I will tell you a smelly story.

Nowadays, the water in Amsterdam’s canals is cleaner than ever before. But four centuries ago, right after the construction of the canal ring, people complained about the filthy water. The stench of rotten eggs caused the inhabitants of the luxurious canal houses to hold their breath every time they stepped outside.  In the Golden Age, the smell of success could only be experienced indoors, behind Amsterdam’s beautiful gables, as the pungent odor on the streets was simply disgusting. It was awful in summer, especially when the water levels were low. The canals were, quite literally, open sewers. Whether it was from private houses or businesses, everyone simply threw their waste into the canals.

In the Golden Age, the smell of success could only be experienced indoors, behind Amsterdam’s beautiful gables, as the pungent odor on the streets was simply disgusting. It was awful in summer, especially when the water levels were low. The canals were, quite literally, open sewers. Whether it was from private houses or businesses, everyone simply threw their waste into the canals.

The Prinsengracht is the longest canal in the canal ring and suffered most, as it became stagnant and foul-smelling. For centuries, the only solution to the stench nuisance was to get rid of the canal and fill it up with sand. Seventy canals were filled up this way. Since the Prinsengracht was important for the transport of goods to the many warehouses, filling up the canal was never a serious option.

Continue along Prinsengracht.

15. Leidsegracht & Peter Goemansbridge

Centuries ago, a number of narrower connecting canals were dug perpendicular to the Herengracht, Keizersgracht and Prinsengracht. This smaller canal to your left and right was named after the city of Leiden. When the Leidsegracht was constructed in 1615, it formed the southern border of Amsterdam. On this spot, a heavily fortified rampart was built to keep out potential attackers, a row of high timber stakes ensured that the enemies were kept at bay. Following the 1658 expansion of Amsterdam, the inhabitants of Leidsegracht 97, at the other side of the canal further to the right, showed the fact that they lived in ‘the newest part of the city’ with this striking gable stone.

In 1949, while walking across this bridge, singer-songwriter Pieter Goemans was inspired to write the famous song ‘Aan de Amsterdamse Grachten’ (‘On Amsterdam’s Canals’). It is one of the most popular songs celebrating the city and the most played music on street organs across the Netherlands. When the author died in 2000, his ashes were scattered here in the canal. The plaque on the bridge commemorates his contribution to the Dutch musical legacy. In 2008, the bridge was named after Pieter Goemans.

Don’t cross the Peter Goemansbrug, but cross the bridge on your left and walk into Leidsegracht.

16. Leidsegracht 51 (KLM-house No. 78)

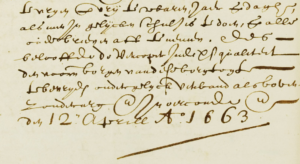

In 1660s, the city’s governors decided to develop the disused land to the south of this canal so that Amsterdam could continue to grow. The plot at today’s number 51 was sold for about 13,000 euros. In 1664, the plague created havoc in the city and a staggering 24,000 Amsterdam people died. Unsurprisingly, the housing market collapsed completely. After a number of years of inactivity, these three identical houses were built, each with a clock gable soberly decorated with garlands. One of these features as KLM House number 78.

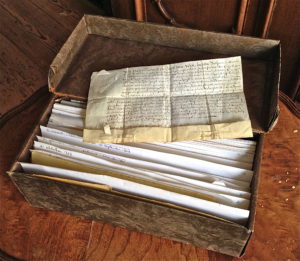

Today, part of the house’s inventory of Leidsegracht 51 is a centuries-old little box containing some forty purchase contracts; all successive inhabitants have kept and passed on their contracts to the next owners. The oldest dates back to January 14, 1671.

Continue along Leidsegracht.

17. The birth house of Cornelis Lely

A bit further, also on the other side of this canal, lies a special house. It’s at number 39. This is the house were Cornelis Lely was born in 1854. He spent much of his childhood and youth on the canal and developed a fascination for water. When he was about 16 years old, the Oranjesluizen, a system of locks outside Amsterdam, were completed and water levels in Amsterdam’s canals ceased to fluctuate with the tide. Towards the end of the 19th century, Lely had become a civil engineer and was appointed Secretary of Water Management. He presented an ambitious plan to cut off the Zuiderzee (South Sea) from the North Sea, turning it into a freshwater lake. Trade on the inland sea had served the Dutch economy well for centuries, but at the same time, raging spring storms had been a constant threat to its coastal towns, villages and agricultural hinterlands. In Lely’s view, the best solution was to shorten the Dutch coastline by cutting off the Zuiderzee from the North Sea with a dike, so that an inland lake was created. He further envisaged to turn parts of the lake into dry areas, so that the country would have more land for farming.

It wasn’t until after the devastating floods of 1916 that Lely’s plans were taken seriously and with a sense of urgency. Taming the Zuiderzee was an unprecedented and ambitious idea. Access to the inland sea, covering 5,900 square kilometers, was to be blocked by a dike of more then 30 kilometers long, bringing an end once and for all to the floodings. In 1927, three years after his death, work on his master plan started. The Afsluitdijk (Enclosure Dam), 30 kilometers long and 90 metres wide, separated the Zuiderzee from the Waddenzee and North Sea to the north.

a sense of urgency. Taming the Zuiderzee was an unprecedented and ambitious idea. Access to the inland sea, covering 5,900 square kilometers, was to be blocked by a dike of more then 30 kilometers long, bringing an end once and for all to the floodings. In 1927, three years after his death, work on his master plan started. The Afsluitdijk (Enclosure Dam), 30 kilometers long and 90 metres wide, separated the Zuiderzee from the Waddenzee and North Sea to the north.

When the final section was completed in 1932, direct access to the North Sea was cut off and the name Zuiderzee (South Sea) was changed into IJsselmeer (Lake IJssel).In 1939, a commemorative gable stone with Cornelis Lely’s portrait was set into the house at Leidsegracht 39, where he was born. He is depicted in between the Zuiderzee and the IJsselmeer.

Continue along Leidsegracht, cross the bridge over Keizersgracht and keep walking along Leidsegracht.

18. Leidsegracht 10 (KLM-house No. 9)

We are almost at the end of our tour. You see that beautiful canal house at your left, at Leidsegracht 10? It was built in 1665. The façade is adorned with opulent decorations such as a lavish wreath of garlands with exotic fruit and flowers. Despite the fact that Amsterdam in the 17-th century was nicknamed ‘a beautiful maiden with foul breath’, due to its polluted canals, the authorities cared for a better and greener atmosphere. From the beginning of the Dutch Golden Age, trees were systematically planted along the new canals. This use of green was a unique and modern feature for a European town.

When designing the Canal District, the city council decided that only half of every plot could be used for building a house. This means that long gardens can be found behind the canal houses, which was a rarity for a city in those days. In the 17th century the gardens of affluent Amsterdammers thrived with brightly colored flowers and plants. However, in later years, it became more fashionable to have landscape gardens with flora in softer colors. Today, gardens in Amsterdam with pastel shades are still popular.

Each June, Open Garden Days are organized in Amsterdam, when quite a number of decorative and landscaped gardens hidden behind the canal houses can be visited (and admired) by the general public.

Continue along Leidsegracht and turn left at the end into Herengracht.

19. Museum of the Canals

Herengracht 386

Right here on your left is the Museum of the Canals. One such garden is situated behind this former banker’s mansion, built in the same year as the canal house we’ve just passed. This grand historic building is now the location of the Museum of the Canals. It opened in 2011 after the Canal District was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. You can explore the rich history of the Amsterdam canals with fantastic 3D animations, models, projections and an interactive multimedia exhibition. Their most asked question is how deep the canals are. After all, the water is so clean that you can even swim in the Canal District. Just like Queen Maxima did a few years ago. The answer to the question is one meter of water, one meter of mud and one meter of bicycles. And it’s a pretty good estimate, even for the bicycles. Every year, 15.000 to 20.000 bikes are retrieved from the canal by the Water Authorities, they end up as scrap metal. And an average of 35 cars go into the water every year. So there is never a dull moment in the capital of our great little ‘Kingdom by the Sea’.

This is the end of our tour. During our walk you’ve seen a lot of boats passing by. You can rent one, if you like, but remember… even on the water, there is a speed limits. You’ll get a ticket if you go faster than 10 kilometers an hour. Every additional half kilometer will costs you a whopping 239 euros. So 11 km. an hour means a fine of 500 euros. If you want to see the city from the water, rent a canal bike. After all, Amsterdam is the number one cycling city in the world and canal biking is a relaxed way of taking in the cities’ unique atmosphere.

If you have enjoyed the stories from ‘Kingdom by the Sea’, then you might be interested in the other audio-tours as well. Have a look at this website or go to the shopping section to purchase your copy of this book.

Mark Zegeling

Author Kingdom by the Sea,

A celebration of Dutch cultural heritage and architecture

Frits Bolkenstein

Frits Bolkenstein