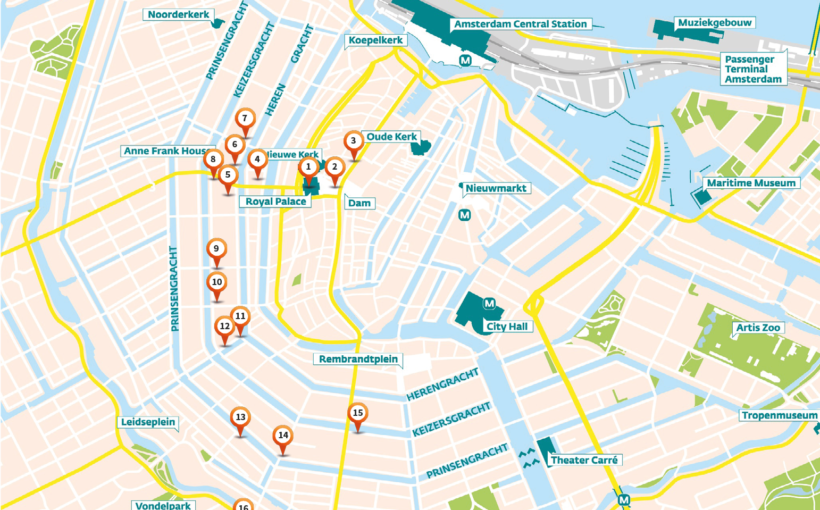

You are about to embark on a grand tour through 500 years of Dutch Design. Amsterdam is the cradle of creativity and home to some of the most innovative architects in history. From Barbados to St. Petersburg, and from Cape Town to Gdansk in Poland; step gables, neck gables and clock gables can be found all over the world. They are the calling cards of Dutch architecture. The book ‘Kingdom by the Sea’ contains the amazing stories of more than hundred monuments which modelled for the world-class miniature house collection of KLM Royal Dutch Airlines. With its series of Delft blue souvenirs, KLM pays homage to five centuries of architectural history and Dutch design of timeless significance.

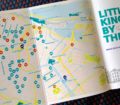

This audio guide take you on a tour through time, along the beautiful canal houses and landmark buildings which served as inspiration for the iconic KLM collection. The route is customized and developed for people who don’t have an in-depth knowledge of architecture. So, are you ready to meet some of the greatest names in Dutch architecture?

1.The Royal Palace (KLM-Collector’s item)

Dam/Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal 147

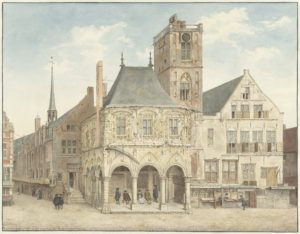

This monumental building was originally designed as a city hall rather than a palace. In 1648, the old medieval town hall had become drab compared to the sumptuous mansions lining the canals. At the height of the Dutch Golden Age, Amsterdam was the most important commercial center in the world, so a modern city hall was needed to reflect the city’s new status.

Jacob van Campen was chosen as the architect. He had convinced the city’s four mayors by presenting a grand design in the Dutch classicist style: classical forms and tight symmetry combined with ornamental details from the Greek and Roman building traditions. According to the architect, Amsterdam’s new city hall should reflect divine creation: a miniature universe of symmetry and perfection.

On January 20, 1648, the first wooden pole was driven into the marshy ground, and a total of 13,659 trees were used as the foundations. As the construction work progressed, Jacob van Campen and the mayors had fundamental disagreements over the design. Finally, the architect was replaced by the lesser known timber trader and painter called Daniël Stalpaert.

Upon completion, the city hall measured an impressive 80 by 68 meters, making it the largest non-religious building in the Old World. In 1655, it was officially opened with much pomp and ceremony. The new city hall was called the ‘eighth wonder of the world’.

Before you walk to the other side of the Palace, have a look the impressive tympanum on the front. Well-known artists contributed to the decoration of the City Hall, such as the Antwerp sculptor Artus Quellinus. A second tympanum at the rear of the building has the same grandeur. It is crowned by the ‘Maiden of Amsterdam’, her arms outstretched to the continents of Europe, Asia, America and Africa, ready to receive their treasures. You can find her at the backside of the Palace, walk to the left of the building, turn right at the corner and continue walking west. At the next corner turn right into Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal.

2. Behind the Royal Palace

Let’s turn around and have a look at some of the modern buildings in the vicinity of the Palace. Let me first tell you a bit about the street you are looking into. This street is called Raadhuisstraat. It was a canal until 1895. At that time Amsterdam began to suffer from modern big city problems, resulting in increasing traffic. The canal was filled in and replaced by a road.

The magnificent building at the right is Magna Plaza, a big shopping center. It used to be Amsterdam’s Main Post Office. It was built in 1895 in a Neo-Gothic and Neo-Renaissance style. You see that building further down the Raadhuisstraat, next to Magna Plaza? It is called The White House because of its white glazed bricks. It was built around 1900, in a Jugendstil style.

At the other side of the street, at the corner on your left, you see the former center of Dutch telecom service PTT, built in 1924. The architect was inspired by the Larkin Administration building in New York, designed by the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The historic building is now a Food Plaza, and there’s a hotel is on top, the Doube W, with its own outdoor swimming pool and skybar.

Cross the street and walk along Raadhuisstraat to the west and cross the bridge.

3. Dutch India Bank

Singel 250/Raadhuisstraat

On the corner to your left, you see another another grand monument. In 1910, this building was designed in Neo-Classicist style by the same architects who designed Royal Theater Carré (also a KLM House special edition). This building along Singel canal used to be the headquarters of the Dutch India bank.

Continue along Raadhuisstraat and turn right before the next bridge into Herengracht.

4. Herengracht 203 (KLM-house No. 53)

This canal is called The Herengracht, or Gentlemen’s Canal. It is the shortest of the three main canals of Amsterdam. The other canals are called Keizersgracht (the Emperor’s Canal) and Prinsengracht (the Prince’s Canal).

The Herengracht was designed to attract the wealthy. In the 17th century, the crème de la crème of Amsterdam’s elite built their homes along this canal. The plots sold by the city were widest on the Herengracht. Some of the richest buyers acquired two or three adjacent plots and built truly palatial houses. You can see them here.

The construction of the canal ring prompted many members of Amsterdam’s elite to move from the old city center to the new ‘Gold Coast’. Following the allocation of the land in 1618, wine merchant Wolphert Webber commissioned the most celebrated architect of the day, Hendrick de Keyser, to build a prominent merchants’ house at number 203, which is on your right. It is also a KLM House, No. 53.

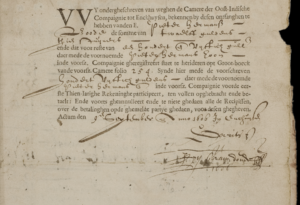

This Wolphert Webber was one of the first shareholders of the Dutch East India Company. Although he had gather a considerable fortune during his lifetime, Webber lived way beyond his means, running up huge debts. He died a destitute man. Centuries after his death, his descendants in the USA started to search for a hidden inheritance worth millions. Wolphert Webber, it was believed, was the bastard son of none other than William of Orange, the father of the Dutch nation. No less than eighty family members in the USA staked a claim on the fortune, all without success.

5. House Bartolotti

Herengracht 172

Do you notice the flamboyant merchant’s house on the other side of the canal (on number 172), with its stunning façade in red brick and white stones? This building was also designed by Hendrick de Keyser. In the early decades of the 17th century, he was the most important sculptor and leading master builder in the country. After an inspiring study trip to London in 1607, he introduced classical elements into Dutch architecture and was instrumental in establishing an Amsterdam Renaissance style. Today, this architectural landmark is the main office of the Hendrick de Keyser Association. The organization is the guardian of Dutch architectural heritage; it acquires historic properties which are rented out after restoration.

Continue along the canal and cross the bridge, turn left, so that you’re walking back along the other side of the canal.

6. The first neck gable

Herengracht 168

Further down, on your right, you’ll see a very special house. It was the first neck gable in Amsterdam. In 1607, in the year architect Hendrick de Keyser went to London to study, Philips Vingboons was born. He started his career as a painter, and later became an architect. He was one of the competitors of Jacob van Campen to build the new city hall on the Dam Square.

In 1638, Vingboons made a personal statement by delivering a design for a new kind of facade that set tongues wagging. He simplified the traditional step gable of the house at Herengracht 168, further to your right, into a classical linear form with two rectangles. The neck gable led to a small revolution in the Dutch building style. The combination of modern and classical became the talk of the town and was widely imitated until around 1665.

Continue your walk on Herengracht, to the Raadhuisstraat. At the corner, turn right and we will fast forward to the last decade of the 19th century.

7. Monumental housing complex

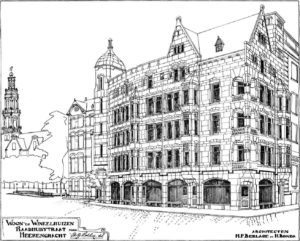

Herengracht 184/Raadhuisstraat 30-32

Toward the end of the 19th century, new buildings on the Raadhuisstraat had to meet strict criteria to ensure that this road would be a worthy entrance to the center of Amsterdam. In 1897, architect Hendrik Berlage was commissioned to design a housing block at the corner of Herengracht and Raadhuisstraat, where we now stand. The ground floor was intended to house four luxurious shops.

Berlage, the godfather of modern Dutch architecture, was a socialist by nature. Not only that, he was also an idealist. To him, architecture was an expression of human feeling. Berlage felt that society had in some way lost the spiritual values which tied communities together. He wanted to make luxury goods such as those sold here available to the ordinary man in the street. His sober building style did not need extravagant decoration, yet in order to build a bridge between art and architecture, Berlage had stylized ornaments made for the façade of the complex. The building was treated as a sculpture, with curved corners, oddly placed windows and an ornamental tower.

Berlage’s work had a great and lasting impact on modern architecture, and heavily impacted on the Amsterdam School movement, which linked architecture with socialist ideals.

Let’s walk to the end of the block and stand still at number 34. Above your head, at the base of the tower, you see a sculpture. Do you see what animal it is?

Right, it is an elephant.

Continue along Raadhuisstraat to the west.

8. Monumental shopping gallery

Raadhuisstraat 21-55

So this is the Raadhuisstraat. You see that monumental shopping gallery across the street? It was designed by Dolf van Gendt, and built in 1896, in a sober Art Nouveau style. Van Gendt is the architect of many famous buildings. At the turn of the 20th-century, he was Amsterdam’s most popular architect. Near the end of this tour, we’ll see the highlight of his oeuvre: The Concertgebouw building. Have a look at the details of the Raadhuisstraat gallery. And do you see the animals, especially on the roofs?

You see the church tower further down the street? It is the tallest church tower in the city, measuring 85 meters. The Westertorwer was designed by Hendrick de Keyser and built between 1620 and 1631. He is best known for the design of this church, the Zuiderkerk and the Mint Tower. These monumental buildings are major landmarks in Amsterdam’s inner city. Hendrick de Keyser died in 1621, a year after the work on the Westertoren began. The job was finished by his son Thomas.

You see the church tower further down the street? It is the tallest church tower in the city, measuring 85 meters. The Westertorwer was designed by Hendrick de Keyser and built between 1620 and 1631. He is best known for the design of this church, the Zuiderkerk and the Mint Tower. These monumental buildings are major landmarks in Amsterdam’s inner city. Hendrick de Keyser died in 1621, a year after the work on the Westertoren began. The job was finished by his son Thomas.

Cross the bridge and turn left into Keizersgracht.

Let me tell you a bit more about Amsterdam and its architure.

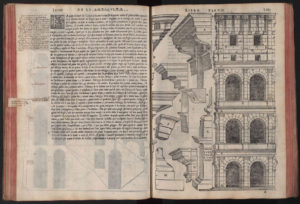

Amsterdam’s city center is built on ninety artificial islands, all connected by no less than 240 bridges. Because of this remarkable fact, Amsterdam has often been called the ‘Venice of the North’. But the similarities between Amsterdam and Venice do not end there; a number of the designs for Amsterdam’s canal houses were inspired by Venice and her architecture. In 1615, the Venetian architect Vincenzo Scamozzi published his most famous book entitled L’Idea dell’ Architettura Universale. In this book, he tried to unravel the principles of Roman classical architecture and he revealed how to combine different elements to create beautiful forms. Scamozzi’s ideas about symmetry, dimension and scale, as well as the use of symbols from antiquity, made an impression all over Europe. The book became a bestseller and even led to a new building style in the Netherlands, called Dutch classicism.

In the Republic of the United Netherlands, architects Jacob van Campen, Pieter Post and Philips Vingboons became the most important representatives of Scamozzi’s work, even though they put their own stamp on his style. This emerging Dutch classicism was ideally suited to the growing self-awareness of the young republic and symbolically represented its aspirations to be an important cultural force.

In the Republic of the United Netherlands, architects Jacob van Campen, Pieter Post and Philips Vingboons became the most important representatives of Scamozzi’s work, even though they put their own stamp on his style. This emerging Dutch classicism was ideally suited to the growing self-awareness of the young republic and symbolically represented its aspirations to be an important cultural force.

Continue for a while along Keizersgracht and take in all those wonderful gables.Cross the canal here, but stand still on the bridge. Just take in that wonderful house on the other side of the canal. It’s on number 319. You see the historic building with those impressive pilasters? That’s the one. It is KLM House number 69.

9. The White House (KLM-house No. 69)

Keizersgracht 319

You remember the story about the first neck gable at the Herengracht? When that house had just been completed, architect Philips Vingboons was approached by 51-year-old Daniël Soyhier. He had just bought the plot at Keizersgracht number 319. And he wanted to make a statement with a new house. However, Vingboons didn’t want to make an exact copy of Herengracht 168. He carefully designed the merchant’s house, full of style and linear symmetry, based on his Italian-inspired sources of Scamozzi. His design looked like a classical Roman temple. You see it?

On November 23, 1639, a carpenter scratched the date in a supporting beam, indicating that construction of the house had begun. The facade was made of Bentheim sandstone and the house was named ’’t Witte Huys (The White House), because of its color. The property had a raised neck gable with no less than four pediments, two small oval windows in the shape of a bull’s eye, and highly sculptured wings, decorative vases and festoons around the hoist-beam hook.

The house was given even more prestige through the use of Tuscan and Doric pilasters. The half-pilasters create an optical illusion and suggest depth, making the facade appear even grander. It was the first time that Philips Vingboons had added this type of decoration to a domestic dwelling.

Cross the bridge and turn right.

10. Keizersgracht 353

You will know by now that Hendrick de Keyser was the most important architect around 1600. A hundred years later, this role was taken over by Anthonie Turck, who was actually a sculptor. Turck left his mark all over Amsterdam; his striking and monumental ornaments often caused a sensation in the world of sculpture.

His invention of a richly decorated, raised cornice, and the neck gable with floral motifs in the scrolls, unleashed nothing less than a sculptural revolution. An example of this style can be seen at Prinsengracht 305, not too far away from here. KLM House number 62 is a Delftware replica of that monument, built in 1720 (see photo above).

Slightly bit further from here, Keizersgracht 353, you can see his house. Its facade is graced by a self-portrait sculpture of Antonie Turck.

Cross Huidenstraat and continue along Keizersgracht.

11. Municipal stonemasons’ yard

Corner Keizersgracht/Leidsegracht

Slightly further down, at the corner of the Keizersgracht and Leidsegracht, this site was once the location of the municipal stonemasons’ yard. In 1648, blocks of stone were carved here for the new city hall, now known as the Royal Palace. It was also the place where sculptor Quellinus made the ornaments and sculptures to decorate the façade of this national landmark.

At the corner, turn left into Leidsegracht.

12. The house of Barent Graat (KLM-house No. 9)

Leidsegracht 10

In 1665, the artist Barent Graat designed his dream house, and adorned it with one of Amsterdam’s first clock gables. Barent Graat was not only an outstanding painter and draftsman, but he designed the ornaments as well. The facade of Leidsegracht 10 is adorned with opulent decorations. The artist showed his capabilities in the design of the decorative elements, seen clearly in the l’oeils-de-boeuf or bulls’ eyes. The small, round loft windows are works of art in themselves, with delightful bows carved in sandstone.

As a painter, Graat was admired by his colleagues for his professionalism and refined technique, but he was virtually unknown among the general public. Today, a number of Graat’s works can be seen in The Rijksmuseum, and some of his paintings are included in the art collection of Queen Elizabeth.

At the corner, turn right and cross the bridge. Continue along Herengracht. Turn right here into Leidsestraat. Here you can do some shopping. Keep walking along Leidsestraat. Cross the canal and turn left into Prinsengracht.

13. An Amsterdam-School façade & luxurious canal mansion (KLM-house No. 42 and No. 43)

Prinsengracht 514 and 516

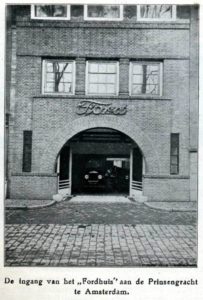

Now, we are approaching two very interesting houses next to each other: Prinsengracht 514 and 516. Let me start with the first one on the right. In the 19th century, this building at 514 was a masonry shop. The former stables behind it served as storage, and blocks of Bentheim and Gobertange sandstone, slate and marl were piled high. However, in the early 1920s, the property became a showroom for the American car company Ford.

Architect Harry Elte was commissioned to oversee the renovation, which included also an extension to house a parts warehouse and workshop. Before that, between 1899 and 1909, Jewish architect Harry Elte had worked as a draughtsman for the great Berlage, by whom he was influenced. And you can see it now. The entrance was given a distinct, Amsterdam-School brickwork round arch, a style which you can also see in the recessed sidelights and first-floor windows. Elte established his name as an architect with the design of the national football stadium in Amsterdam-Zuid, which could seat 30,000 people. His designs show the influence of Berlage, Dudok and the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. In the nineteen twenties and thirties, he designed twelve synagogues. During the Second World War, the Nazis prohibited Elte from working as an architect, because he was Jewish. He was arrested and taken to Westerbork transit camp, where he was imprisoned and forced to work in the engineering department. Later, he was deported to a concentration camp in what is now the Czech Republic, where he died on April 1, 1944.

Let’s look at its neighbour, Prinsengracht 514. Well, it does not seem that special, does it? But let me tell you, behind its façade waits a hidden gem. The building dates from around 1865, and despite the various alterations, its classical cornice has been conserved. The well-known Dutch architect Cees Dam was commissioned to redesign the facade and, in 1973, an extension was built to accommodate a studio.

In 2005, the building changed hands and the new owner stripped its interior. Only the 19th-century façade, modified by Cees Dam in the seventies, was preserved, and everything behind it was demolished. Behind the façade is a whole new world to discover. After the house was rebuilt, Prinsengracht 516 became a modern and very luxurious canal mansion with a swimming pool, sauna, bar, wine cellar and cinema.

Continue walking toward the bridge, and cross it. Then turn left, cross the bridge over the canal and continue into Nieuwe Spiegelstraat.

14. Kramer Art & Antiques

Prinsengracht 807

You see that antique shop at the corner in front of you? That’s Kramer Art & Antiques shop. You know that I’m guiding you on this walk past a number of architectural gems, which models for the iconic Delft Blue collection of miniature houses. Ever since the 1950s, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines presents its Business Class-travelers with a miniature replica of a canal house or a national landmark as a souvenir. The collection contains 96 different miniature houses and 8 special editions, and together they are representing 500 years of Dutch architectural history. If you want to see the entire collection, or wish to buy a Delft Blue miniature yourself, have a look inside this shop. The store not only sells KLM houses but also has a wonderful selection of Dutch tiles from the 15th century onwards.

After browsing at Kramer Art & Antiques, continue along the Nieuwe Spiegelstraat. Turn right into Keizersgracht. Cross the street (Vijzelstraat) and continue along Keizersgracht.

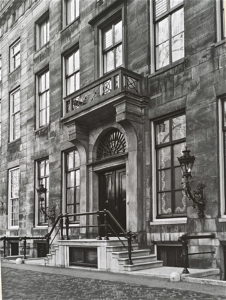

15. Museum van Loon (KLM-house No. 83)

Keizersgracht 674

I know it’s a bit off the track, but I’d like to show you the work of another remarkable architect who was responsible for the design of numerous buildings in the canal district. Just continue walking Keizersgracht 674. This sumptuous canal house is the property of a distinguished noble family and now accommodates the Museum Van Loon. In the 17th-century, these kind of residences were not only places to live in, but also a way to impress business colleagues. Arms trader Jeremias van Raey was one such man who liked to dazzle his clients. In 1672, he gave the order to build an ‘extra splendid house’ along the Keizersgracht canal. The mansion, designed by architect and military engineer Adriaan Dortsman, is exemplary of the Dutch Classicist style. He is commonly associated with the so-called ‘flat style’ facades, a later development of Dutch Classicism.

The statues along the roof’s edge of Keizersgracht 672 and 674 refer to the origins of the fortune of Jeremias van Raey, and to the turbulent times in which the property was built. Standing guard over the inhabitants are Roman gods and goddesses. From left to right: Mars, the god of war; Vulcan, the god of fire; Ceres, the goddess of the harvest; and finally the god of wisdom, Minerva.

From around 1672 onwards, an extremely austere classicism arose to replace the once popular pilaster gables. Architects focused on large undecorated sandstone surfaces and ideal classical proportions. Architect Philips Vingboons, a name you are familiar with by now, started this fashion, but it was Dortsman who made this type of facade more popular.

Walk back the way you came and turn left at the corner into Vijzelstraat. Cross the canal and turn right into Prinsengracht. Turn left into Spiegelgracht and continue walking. Cross the bridge and walk toward the big building in front of you, the Rijksmuseum.

16. The Rijksmuseum

Museumstraat 1

You are now about to enter the Amsterdam museum quarter. It covers an area of about one square kilometer and is home to a concentration of world-class museums and exclusive shops. Without doubt, the Rijksmuseum, the grand building right in front of you, is the most iconic building. Its collection consists of more than one million objects of art and masterpieces from 1200 to 2000. In 1876, when the construction bof this temple of culture began, this area was a meadow just outside Amsterdam, which was a lot smaller in those days. Just imagine that. Under the watchful eye of Catholic architect Pierre Cuypers, a monumental building took shape in a Neo-Gothic style, and incorporating elements of important Dutch historical events. Cuypers’ design sparked mixed reactions; the Rijksmuseum was nicknamed the ‘Archbishop’s Palace’ and the Protestant King William III believed it to be ‘too Roman Catholic and too Gothic’. Initially, he even refused to set foot in the museum on the day it opened in 1885, calling it ‘a monastery’. The architect’s name is also frequently associated with the Amsterdam Central Station, and he designed more than hundred churches across Holland in which his favorite 13th-century French architecture building style played a prominent role.

Continue through the Underpass. Beware of cyclists!

17. Underpass Rijksmuseum

Let’s walk through the passage in front of you. At the back of the building, you’ll see something special. Do you see it? Here, architect Pierre Cuypers has included himself in the grand design, as a sculpture peeking around the corner. On both the inside and outside of the building, the Rijksmuseum is richly decorated with references to Dutch art history. In 1890, the south wing was added to the museum, made out of parts of demolished buildings, that together give an overview of the history of Dutch architecture. This part of the Rijksmuseum is informally known as the ‘fragment building’. The Asian pavilion was designed by the Spanish architects Cruz y Ortiz and opened in 2013, after a grand refurbishment of the museum.

Continue walking towards the big square.

18. Museumplein – Sven-Ingvar Andersson

The magnificent building at the opposite side of the square is called The Concertgebouw, Amsterdam’s world-renowned concert hall, built in the Viennese Classicist style. Its foundation stone was laid in 1882. Let’s walk in that direction. The overall-design of the Museum District was conceived by the Swedish landscape architect Sven-Ingvar Andersson, who, in 2001, integrated the museums and the Concertgebouw building within a public space. As we walk towards the Concertgebouw building, we’ll pass several important museums. The first one on your right hand side is the Vincent van Gogh Museum, dedicated to the works of the 19th-century master.

Continue walking toward the Concertgebouw.

19. Van Gogh Museum

Museumplein 6

On your right is the Van Gogh Museum. After the death of Vincent van Gogh in 1890, his paintings passed through the hands of his family members until his nephew took the initiative of creating a museum for celebrating and displaying such a national treasure.

Architect Gerrit Rietveld was originally chosen to spearhead the project. He was one of the principal members of the Dutch artistic movement De Stijl. Tragically, however, Rietveld died in 1964, a year after the project began. A colleague took over, sticking closely to Rietveld’s previous sketches. When two years later, this architect also died, the project was finally left to be finished with a slightly adjusted design by a third architect.

The museum’s collection is the largest of Van Gogh’s paintings and drawings in the world. It comprises 200 paintings, 400 drawings, and 700 letters by the great and troubled artist. In 1999, an exhibition wing by the Japanese modernist architect Kisho Kurokawa was added. Just as Rietveld, Kurokawa loves geometric shapes. He designed a building with curved lines, based on the outline of an ellipse. The oval coated in granite is a symbiosis between East and West, between straight and curved lines, between order and chaos. Since 2015, visitors enter the museum via a spectacular glass structure. This new entrance building at the Museumplein side was designed by the firm of the late Kisho Kurokawa.

Continue walking toward the Concertgebouw.

20. Stedelijk Museum

Museumplein 10

The next museum on your right is the Stedelijk Museum. It was originally built in 1895 in a Neo-Renaissance style. With its gable end and small tower, the exterior, in red brick with stone dressings, refers to 16th-century Dutch Renaissance architecture. The building was designed by Amsterdam’s municipal architect Weissmann.

The Stedelijk Museum strives to be one of the most innovative and interesting museums of modern art in the world. Over the years, the interior has been regularly modernized and adapted to meet the demands of modern times. In 1938, the hall was literally whitewashed, erasing all memory of the past. A century after it opened, Weismann’s building still offers comfortable galleries with splendid natural lighting. In the first decade of the 21st century, a boldly contemporary new building was constructed to house the museum’s temporary exhibitions. Although the new building is unmistakably different in appearance from the original structure, it matches the scale of the 1895 building and has a direct, seamless connection to it on all floors.

Continue walking toward the Concertgebouw.

21. The Royal Concertgebouw (KLM Collector’s Item)

Concertgebouwplein 1

Finally we reached the highlight of this tour, the Concertgebouw, that magnificent building in front of you. In the 1880s, a number of wealthy people had the idea of having a concert hall built. Pierre Cuypers, the architect of the Rijksmuseum, suggested using Dolf van Gent. On this tour, we have already seen a design by this architect, remember? When walking along the monumental shopping gallery on Raadhuisstraat. Both men knew each other well. They had worked both on the Amsterdam Central Station. Van Gendt was already a celebrated architect, but the Concertgebouw would become his Magnum opus.

Van Gendt meticulously studied the building plans of the Neues Gewandhaus in Leipzig, Germany, known for its excellent acoustics. Furthermore, he was inspired by the principles of Greek and Roman architecture. The foundation stone was laid in 1882, but it was not until 1888 that the Concertgebouw was opened. And it wasn’t even finished then.

The Main Hall, with its flowing lines and rounded corners, could accommodate about 2,000 people. Because of its dimensions of 44 meters long, 27.5 meters wide and 17.5 meters high, the concert hall was especially suitable for classical music from the late romantic period, and less for chamber music. However, the building was not exclusively used for classical concerts. In 1894, for instance, a cycling championship took place in the Main Hall. In the mid-nineteen eighties, the Concertgebouw was expanded with the inclusion of a modern wing by architect Pi de Bruijn.

There was quite a bit or resistance to the design, but this was silenced with the argument that the wing was intentionally made of glass in order to reflect the original building. In 1988, during its centenary, the Concertgebouw Orchestra got the title ‘Royal’ added to its name to underline its status and cultural significance.

The Concertgebouw, together with the Symphony Hall in Boston and the Great Hall of the Musikverein in Vienna, is considered to be one of the top three concert halls in the world.

Turn back and walk north to the Stedelijk Museum. On the intersection of Van Baerlestraat/Paulus Potterstraat turn right and continue walking.

22. Backside Stedelijk Museum

Paulus Potterstraat 13

You’re now at the back of the Stedelijk Museum. Or should I say the front? Ah, well. But as we walk, look to your right. As a tribute to the great names in Dutch architectural history, you’ll see a number of statues of the architects whose design we have come across today. The first one you see is Jacob van Campen, the architect of the Royal Palace and the founding father of Dutch Classicism. The last one is Hendrick de Keyser, who created his own style: the 16th century Amsterdam Renaissance Style.

Continue along Paulus Potterstraat.

23. House of Bols

Paulus Potterstraat 14

We have almost come to the end of our architectural tour through Amsterdam. Our final stop is across the street at number 14. The building is from 1902 and was designed by architects Ludwig Beier and Jacob van Noppen.

But most importantly, it is the House of Bols Experience. And of course, this is a KLM House special edition.You know that every Delft blue KLM House contains Dutch genever. It is the juniper-flavored national liquor of Holland, from which gin evolved. It is provided by the Bols company. The Bols company was established more than 400 years ago and is the largest distiller of genever in the world. Why don’t you go inside? They have a special room dedicated to the KLM Houses collection.

During our walk, we have seen a lot of interesting houses and I hope you’ve enjoyed their stories. Now you know who designed the first neck gable and what the Dutch classicist style is. If you like to read more fascinating stories, then visit the shop of this site, where you can buy online the book ‘Kingdom by the Sea, a celebration of Dutch cultural heritage’ or order your copy in a bookstore near you.

Mark Zegeling

Author Kingdom by the Sea,

A celebration of Dutch cultural heritage and architecture

Frits Bolkenstein

Frits Bolkenstein